Safarāt Giving Back - Blindness in Nuristan

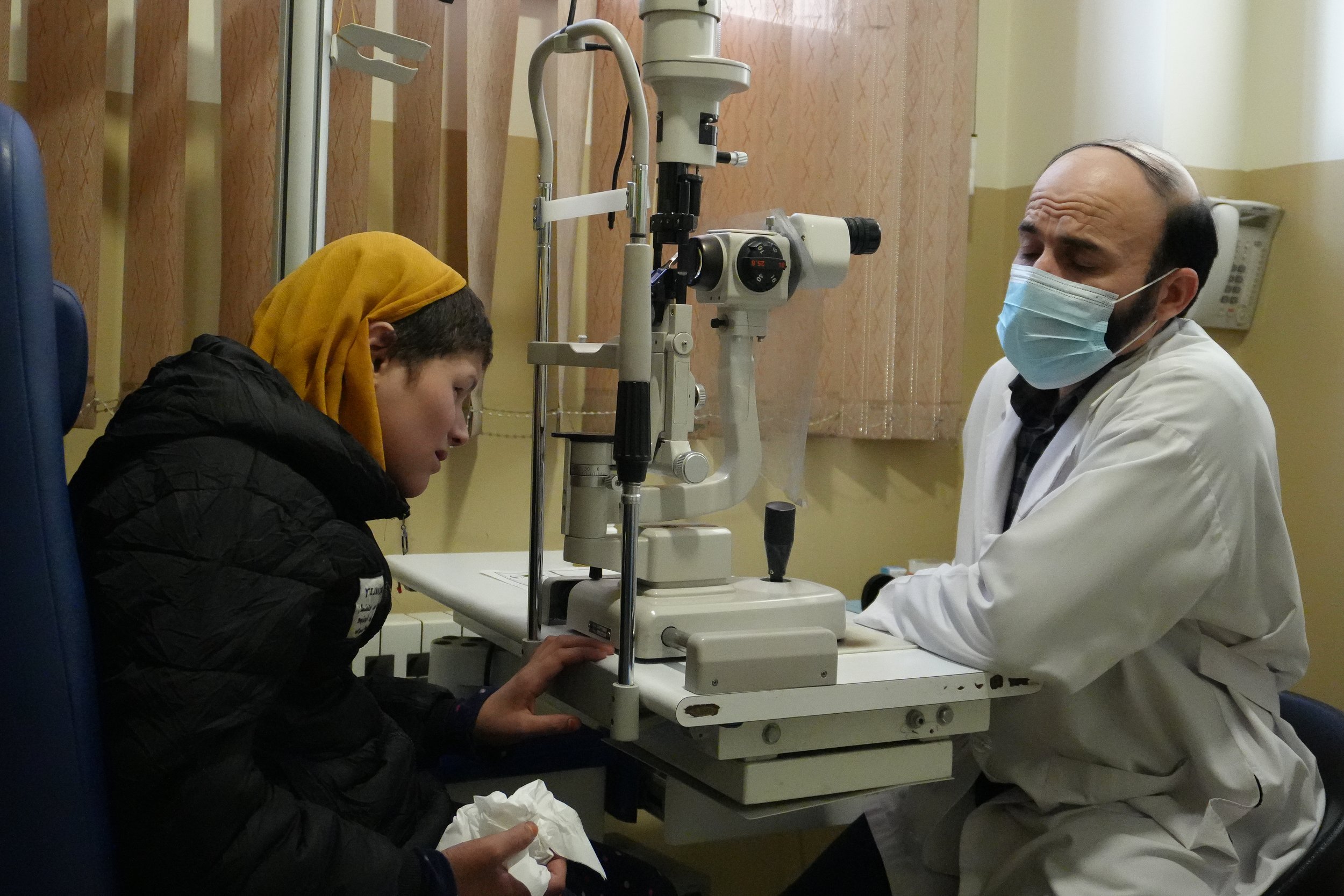

Subhabia from the Kamdesh valley having eye tests in a private eye hospital in Kabul. In theory Afghans qualify for free treatment in public hospitals - but the reality is for many in remote areas, their access to even the post basic of primary medical care is nil.

For years I travelled the world as a photojournalist, dipping in and out of people’s lives offering the suffering the chance to “tell their side of the story.” I rehearse the well worn Faustian pitch on the doorstep, before another grieving mother gets a knock on her door. A request to share her pain in return for a brief slither of recognition for her sacrifice. A fleeting visit from the Vulture Club, washed down the news plughole less than a day later.

And whilst it’s important not to over labor our currently modest contribution in Afghanistan, it’s why I often chuckle when journalistic colleagues question me on the ethics of our project. My hope is that Safarat helps continue to build sustainable livelihoods in places where people have little economic hope and it’s why I still firmly believe that Afghanistan’s main problem isn’t violence, it’s poverty.

But simply hoping that our Safarāt’s economic success trickles down and helps our local partners isn’t enough.

Joe hiking above Upper Kamdesh village, on a mountain path leading to the Waygal Valley in summer 2023.

This Spring I visited Nuristan for the first time on a short survey of the remote province in preparation for out upcoming expedition in 2024 (you’ll get an email about this in the next couple of days…I promise!). It was whilst trekking through the mountain villages of the Hindu Kush that I noticed an unusually high level of juvenile blindness in the hamlets we were passing through. Every small community seemed to have children with cataracts, glaucoma or some kind of eye condition. I was shocked.

I wondered if there might be some easily explainable cause for this glut of eye disease and blindness. When I got back to Kabul I emailed anyone and everyone I could think of who had been involved in eye surgery. I spoke to members of NGO’s, a friend’s wife who is a British ophthalmologist, eye doctors in Kenya and a dozen other experts about the problem.

The responses were broad and vague. Nobody had any idea why or if children in Nuristan were suffering from an abnormally high level of blindness. None of the kids we had photographed had ever met a doctor, never mind an eye specialist.

One NGO who provides mobile eye clinics in the country mentioned that they were seeking funding to run a primary eyecare project in some nearby (and less remote) provinces. Another mentioned that they were hoping to run some kind of survey of Nuristan in 2024. It all sounded a little unclear.

I looked at my bank balance ominously (Safarāt is still running at a loss – book now!) and made a rash decision. It’s how three Nuristani children found themselves at a private eye hospital in Kabul this week, having their first ever eye tests and assessment after making the long journey from their mountain homes.

8 year old Abdullah was one of the first children we met in Kamdesh in the summer of 2023. His father is disabled himself. Sadly his eye condition was no treatable by the doctors in Kabul - and his vision will probably continue to deteriorate.

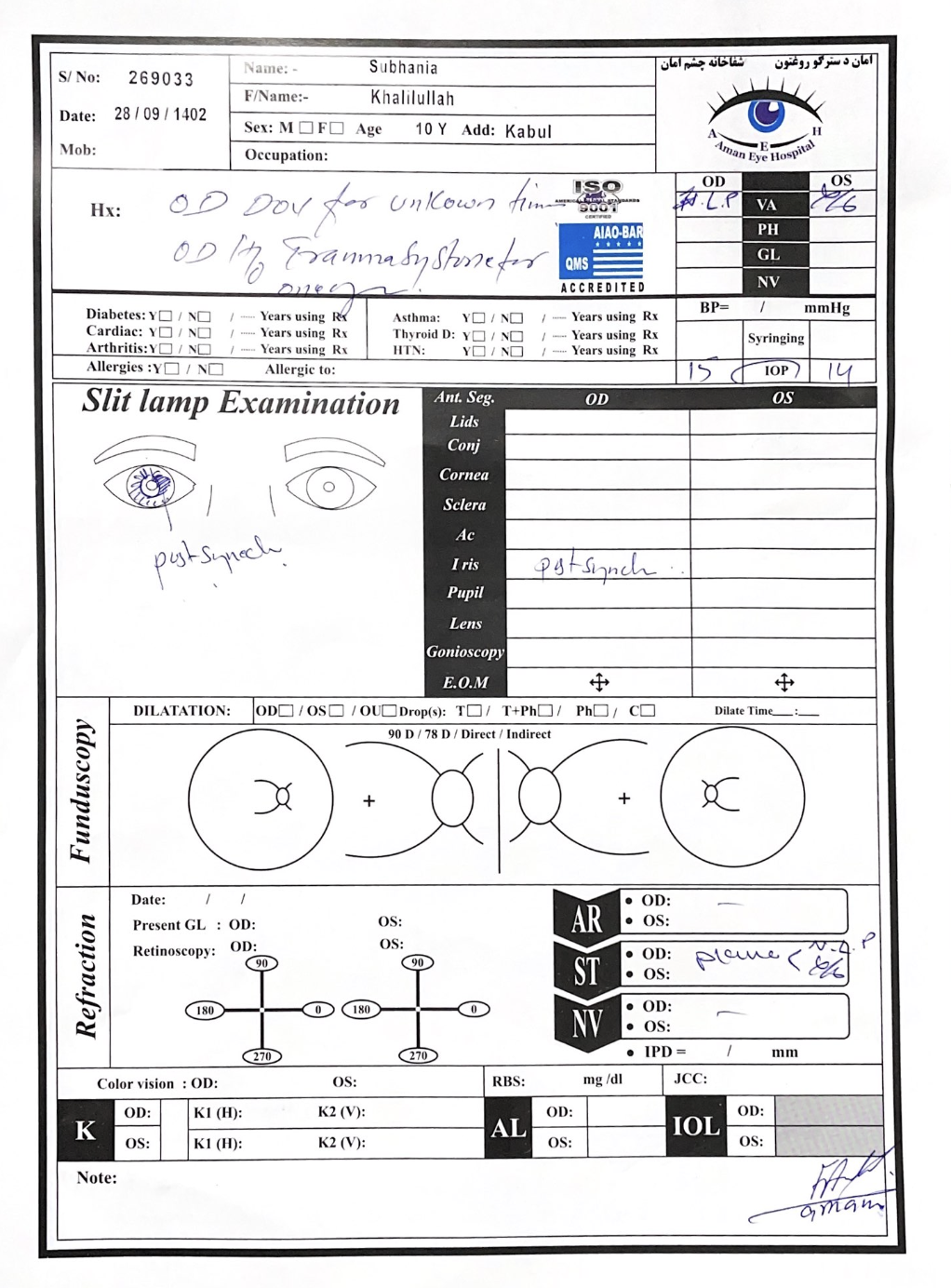

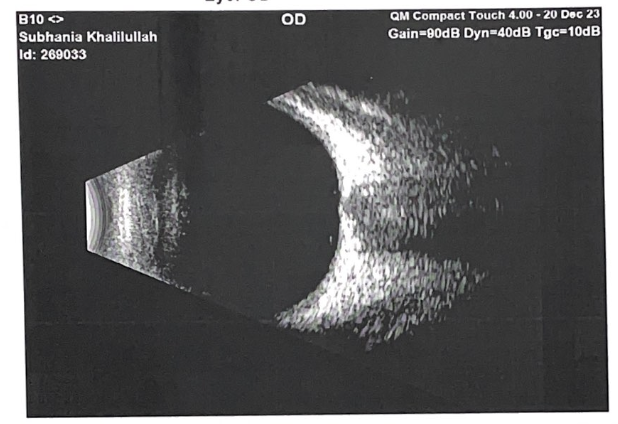

Subhabia who is 10 years old started to lose her sight in her left eye after being hit in the eye with a stone resulting in a traumatic cataract. Abdullah who is 8 was one of the original children we saw struggling with his sight in a hamlet near Mandigal in the Kamdesh valley- he has suffered with itchy, misty eyes since he was three. He has never seen a doctor for any issue.

The pair also travelled with 8 year old Mahboba who is almost totally blind after suffering damage to her eyes from a simple infection – a condition which had it been caught early would have been treated by simple eye drops. She now faces a lifetime of total blindness.

After their appointments at the Amani eye hospital it was decided that both Mahboba and Subhania’s eyesight could be considerably improved by surgery and both will undergo treatment at the end of January paid for by Safarāt. The pair are the first direct beneficiaries of Safarāt and a promise that going forward at least 10% of our profits will be put towards benefitting individuals in need in Afghanistan.

You might be sitting at home and wondering if our (…and your) money might be channeled in a more focused way into a project or through an NGO that can help more people. The answer (as ever) Is complicated and one that we will give more thought to as the year progresses. For now Safarāt remains about making small change in Afghanistan for individuals, whilst still encouraging more glacial paced macro change in the long term.

For now helping individuals fits well into our dedication to listening to people’s stories and helping them to write a better new chapter.